Direct Hit on the USS Hughes

On December 10th, the USS Hughes left Ormoc Bay and returned to the Eastern side of Leyte Island, this time as part of a patrolling mission in Surigao Strait. The mission, also known as picket duty, was considered routine and involved cruising around the area trying to pick up enemy planes on their radar screens that couldn’t be detected by the land-based radar due to the mountainous terrain.

On December 10th, the USS Hughes left Ormoc Bay and returned to the Eastern side of Leyte Island, this time as part of a patrolling mission in Surigao Strait. The mission, also known as picket duty, was considered routine and involved cruising around the area trying to pick up enemy planes on their radar screens that couldn’t be detected by the land-based radar due to the mountainous terrain.

At 4:48pm, only ten minutes into their patrolling assignment, ten enemy aircraft appeared from the clouds over Leyte and began attacking the Hughes. The Hughes managed to maneuver away from the first five bombs that were dropped, but seven minutes into the attack one of the Japanese planes began a kamikaze dive attack. The gunners on the Hughes were able to score multiple hits on the plane during its dive, causing the plane to burst into flames, but it wasn’t enough. The plane, with a bomb still attached, had already gained enough momentum in just the right direction and crashed directly into the middle of the USS Hughes.

The explosion opened a large hole in the port side just above the water line and destroyed their main electrical power supply. The USS Hughes was now in flames and dead in the water. The crew went right to work fighting the fire and 30 minutes later the fire was out. The crew erupted into excitement when four American P-38’s appeared out of the sky and chased the enemy planes away for good. The P-38’s provided cover until darkness came and the tug USS Quapaw was able to tow the Hughes back to safety in San Pedro Bay.

The explosion opened a large hole in the port side just above the water line and destroyed their main electrical power supply. The USS Hughes was now in flames and dead in the water. The crew went right to work fighting the fire and 30 minutes later the fire was out. The crew erupted into excitement when four American P-38’s appeared out of the sky and chased the enemy planes away for good. The P-38’s provided cover until darkness came and the tug USS Quapaw was able to tow the Hughes back to safety in San Pedro Bay.

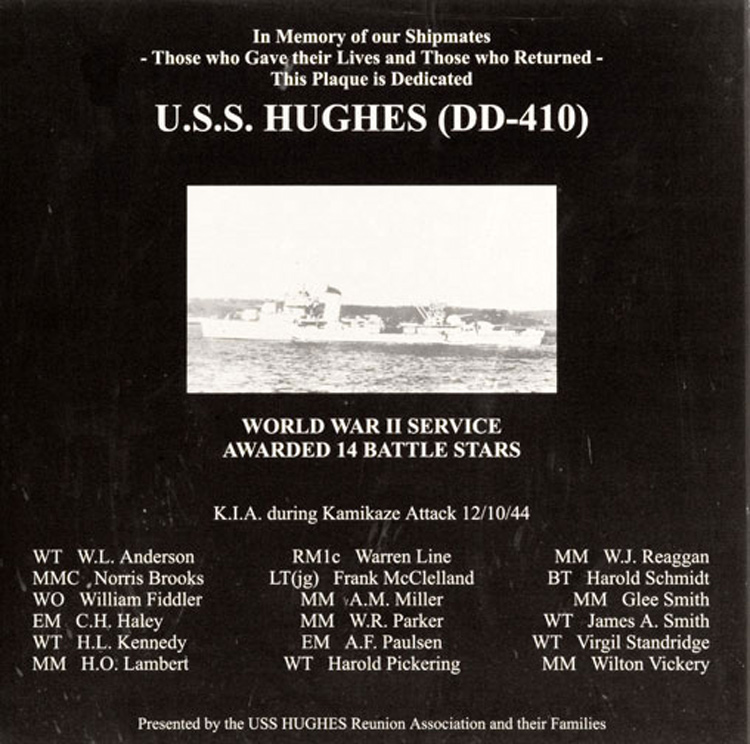

18 brave soldiers of the USS Hughes were killed in the attack on December 10th and another 40 were wounded.

Here is an excerpt from the written account of the events that day by Louis P. Swan, a radio operator serving on the U.S.S. Hughes:

I was working the mid-shift in the radio room that week and decided I would sleep through chow. I lay in the sack listening to the voices coming through the speaker and as soon as I heard the alarm I jumped up. I was fully clothed except for my shoes so I slipped them on, not bothering to tie them.

All hell seemed to break loose. All the 5” 38-caliber guns were firing simultaneously and the 20-mm and 40-mm guns were chattering like a cage of excited monkeys.

The enemy planes were circling just out of range of our weapons and probably deciding who would be the first to die for his glorious Emperor. Suddenly one of the planes broke formation and was approaching the Hughes from our starboard side where he intended to crash into us. However the hail of fire was so great that he swung in a circular motion around the stern of the ship and was coming in on our port side now.

All guns were trained on this lone challenger and tracers could be seen flying all around him. At last we could see that plane’s engine was on fire. We had scored a hit!

All guns were trained on this lone challenger and tracers could be seen flying all around him. At last we could see that plane’s engine was on fire. We had scored a hit!

Everyone was excited and thought surely the plane would either explode or crash into the water. But no, although the plane was burning fiercely, the plane was still heading in a death dive for our ship. We tried evasive action but to no avail.

The plane crashed into our port side midships, gouging a huge hole in the side and main deck. The plane’s engine continued down into the engine-room where a tremendous explosion shook the destroyer.

Mass confusion seemed to reign. Everyone was running around and shouting orders. The skipper, using a megaphone, instructed all hands not manning guns to move aft to the stern of the ship and await further orders. The damage control party went to work putting out the fires that still enveloped the ship. Handy billies were set up in the damaged engine-room to pump the water out of the ship.

Our gun was inoperative so the crew moved aft. As I ran toward the stern, my shoes became entangled in the phone line. I lost both shoes, but kept going. I could feel something sticky on the bottoms of my feet. When I reached the stern I fould that my feet were soaked in blood from the deck. Shrapnel had found its way to our gun mount and several of the crew were bleeding badly, some dead.

The water continued to pour in the hole in our side. A large spool of 5” line had been hurled through the air and landed on the bridge, starting fires there. It seemed the Hughes was doomed. Badly listing from all the water that was pouring into her bowels, it must have appeared to the remaining nine bogies that they would not be needed to finish us off.

All power was knocked out when the boilers in the engine-room exploded. Using his megaphone, the skipper informed all hands that we were not to fire any guns at the remaining planes so that they would think we were finished. However, at the precise moment he was talking, one of the crewmen on 5” gun #1, due to the excitement, kicked out a round at the circling planes (although we had no power, the guns could still be fired manually). It was pitifully short of the target and only seemed to infuriate the enemy planes into further action.

A second plane peeled off from the formation and headed for our ship. Everyone was waiting tensely by their guns for the plane to come into range. They knew that they would have only one chance to knock him out of the skies before he would be on us.

Just when we thought it would all be over, a flight of four of the most beautiful P-38’s came to our rescue. One of the men on duty in the radio room had manned a battery-operated radio that had been left aboard from the Ormac Bay landing and had sent out a distress call. The P-38’s were on patrol duty and had picked up the call and had come to our aid.

As soon as the bogie spotted the P-38’s bearing down on him, he turned and fled back to his formation. With the P-38’s still in hot pursuit, the enemy planes disappeared over the mountains and were not seen again by us. It was later reported that the planes had flown over Leyte Gulf and some of them were shot down while others crashed into the big merchant ships at anchor there.

Below is the memorial plaque that hangs at the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg, Texas that honors the 18 men who lost their lives in the attack on December 10th, 1944:

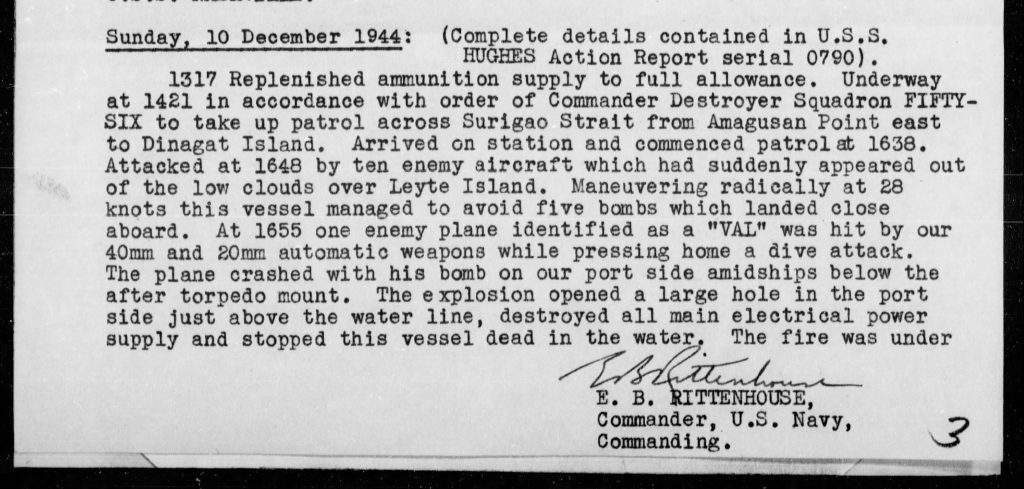

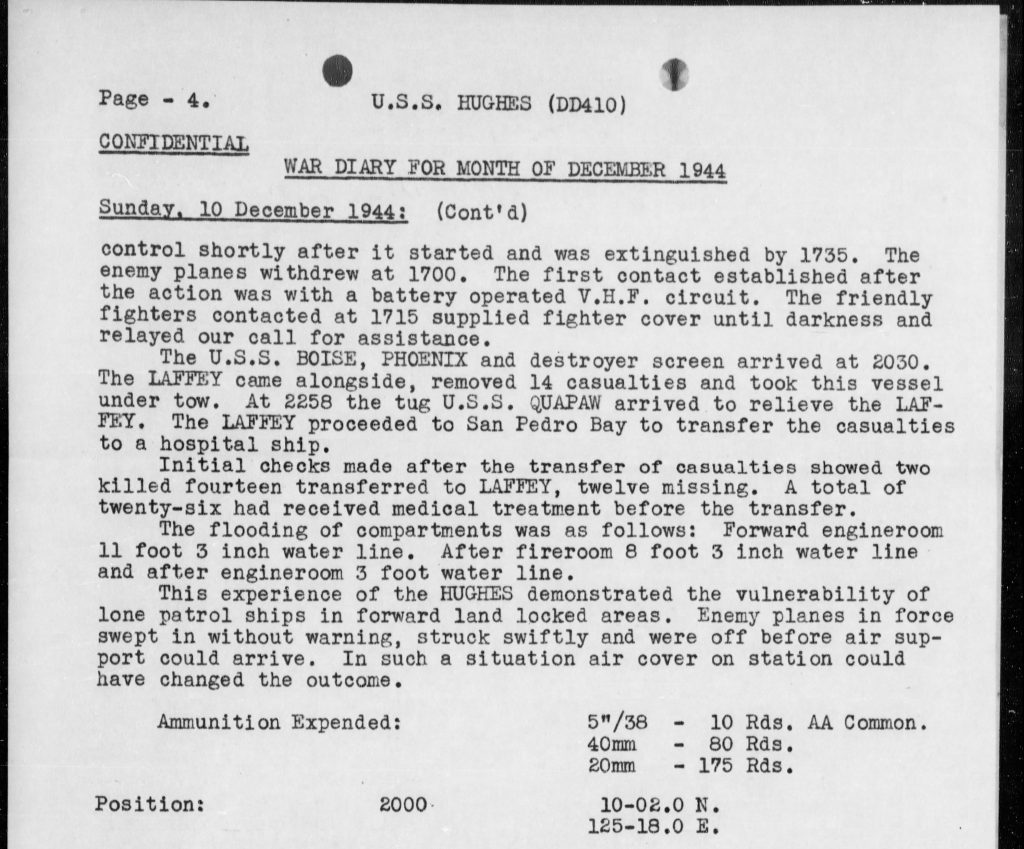

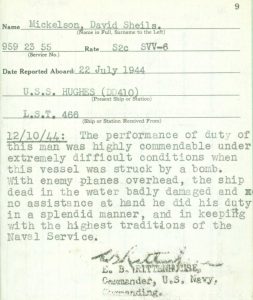

Reports from Commander E.B. Rittenhouse from the day of the attacks: